Nancy Reddy expected to excel at new motherhood.

The graduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison had completed the coursework for her PhD in two years instead of the expected three, and she was accustomed to feeling like a person who was good at things.

Besides, judging by the new moms she’d observed at the farmers’ market in Madison, Wis. — expressions serene as they walked around with babies strapped to their chests — new parenthood didn’t look so bad.

But when Reddy’s newborn son arrived, he wouldn’t latch to breastfeed and spent much of each night screaming.

Instead of seeking the support of others in the same common predicament, Reddy said she isolated herself, certain she was doing something wrong.

“It seemed very clear to me that I was failing,” Reddy told Day 6 host Brent Bambury. “I hold this baby and he cries, and I can’t figure out how to comfort him.”

Looking back, Reddy said she’d absorbed the idea that she would become a so-called good mother — not only by studying parenting books and mommy blogs but through some “mystical combination of hormones and instinct.”

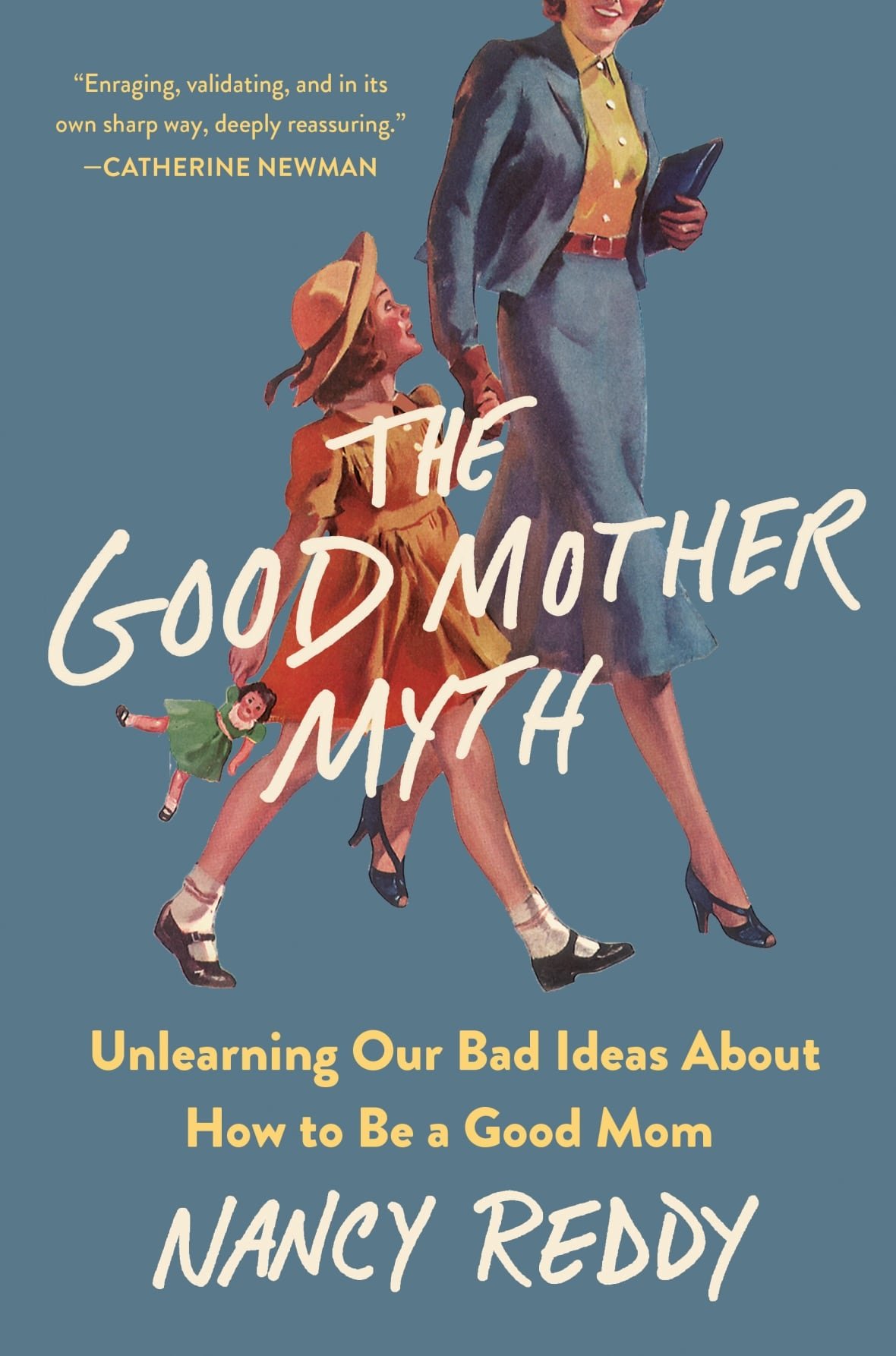

In her new book, The Good Mother Myth: Unlearning Our Bad Ideas About How to Be a Good Mom, Reddy digs into the reasons moms so often feel terrible about themselves when they don’t find every minute of mothering as joyful as books, blogs and Instagram suggest.

To do so, she explores the outdated social science behind a lot of the punishing expectations put on moms. Despite the fact that the majority of mothers with children younger than six hold paid jobs, those societal expectations still suggest the ideal mother is selfless, always available and forever optimizing her children’s lives for success, Reddy said.

Key among those early researchers was Harry Harlow, a psychologist from her own alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, whose research on maternal attachment of infant monkeys, starting in the 1930s, still echoes today — even though it didn’t involve any actual mothers.

In what started with a need to breed a disease-free cohort of baby rhesus macaque monkeys to observe, Harlow began quarantining the infants in individual cages, Reddy explains in her book. When they grew into maladjusted adult monkeys that wouldn’t breed, he changed tack. Harlow equipped each baby’s cage with two wire cylinders, one left bare and the other warmed by a light bulb and covered in terrycloth.

Some babies would get their food from the wire “mother” and others from the terrycloth version, but no matter where their food came from, Reddy said, the babies clung to the fabric-and-light-bulb surrogate.

Even though these “mothers” were actually inanimate objects, Harlow reported his findings as proof that human babies needed constant contact and comfort.

Harlow wrote that he had made the “perfect monkey mother,” Reddy said, “someone who was soft, warm, tender, available 24 hours a day.”

“And I think that image has really stuck with us, that that’s what a baby needs.”

What wasn’t well reported, Reddy said, is how those baby monkeys fared in the long run.

“It turns out, actually, that having this ‘mother’ who was always there and not having any peers makes for really profoundly disturbed monkeys. They actually do better if they have other monkeys they can play with.”

Harmful ideas

Reflecting back on her own experience, Reddy said she now understands that holding a screaming newborn isn’t much fun for anybody. “But I really thought that being a good mother would mean that I wouldn’t mind, that I would just love him so much that everything else would kind of fade away.”

Christina Rinaldi, a psychology professor at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, said these ideas can be really harmful for moms.

“The literature has coined the term ‘the motherhood myth,’ because it is more or less something that’s culturally devised,” said Rinaldi, who holds a PhD in applied child psychology. She said these ideas have been taken to an extreme that suggests nurturing “is a 24/7 kind of job.”

“And it really kind of does not hold space for the fact that mothers are individuals and have their own needs and well-being to take care of…. Nor does it acknowledge that there are other key individuals in children’s lives as well.”

British psychiatrist John Bowlby is another mid-20th-century researcher whose work still impacts motherhood today, Reddy said. He seized on Harry Harlow’s research as the scientific foundation for what would later become Bowlby’s attachment theory, which still has a strong grip on how parent-child relationships are understood.

After the Second World War, he was commissioned by the World Health Organization to travel to Europe and North America and report back on what the children who had survived the war needed most. His answer was a warm, continuous relationship with a mother who would never abandon them, Reddy said.

“And it’s especially striking to me in that context, because those children were traumatized by all kinds of very real material things. A lot of them were homeless. They had seen bombings. It was not, in fact, their mothers who were to blame for their trauma.”

A narrow view of motherhood

Another problem with messages stemming from the work of these mostly male social scientists, Reddy said, is that they operated from an assumption that a so-called good mother was married, straight, white and middle class. “If you don’t fall into one of those categories, you’re kind of automatically set aside.”

Tanya Hayles said she felt that when she was expecting her son, who is now 12.

“There was times during my pregnancy where I wore a fake engagement ring because I knew that, if I’m by myself but it looks like I’m married, then I’m just a married woman out in the world by herself, as opposed to an unmarried woman by herself getting on the bus to go to work or to go to the store,” said Hayles, who went on to found Black Moms Connection in Toronto.

There are a lot of prejudices about Black women, she said, including the assumption that they’re all single mothers. “And I hated that I was going to feed into some people’s notions of that stereotype.”

The social media factor

Adding to the ways these messages reach mothers today is social media, where mom influencers earn a living performing an organized and esthetically pleasing version of motherhood, Reddy said.

Christina Arseneau, a mother of three children aged six and under who works about 50 hours per week at a public relations agency in Toronto, said she’s learned to set aside the pressures associated with what other mothers post on platforms like Instagram and TikTok.

“I see friends burning themselves out in the month of December doing a daily elf on the shelves,” Arseneau said, referring to a popular toy that some parents move into elaborate new positions each night during the Christmas season to keep up a ruse that the doll is reporting back to Santa.

“My kids are like, ‘Where’s our elf?’ So it does definitely make you feel a little guilty, but at the same time, I have to cut the excess because I’d rather spend time with them than research crafty ideas.”

Reddy said she hopes one of the messages moms take away from her book is the importance of asking for help.

“When you ask for help, whether it’s, ‘Can you hold this baby for a minute?’ or ‘Can you get me something at the store?’ or ‘Can you listen to me tell you what a hard time I’m having?’ that’s actually how you build community,” she said.

“When I showed up as my messy self and talked about how I was doing, that was how things started to get better.”